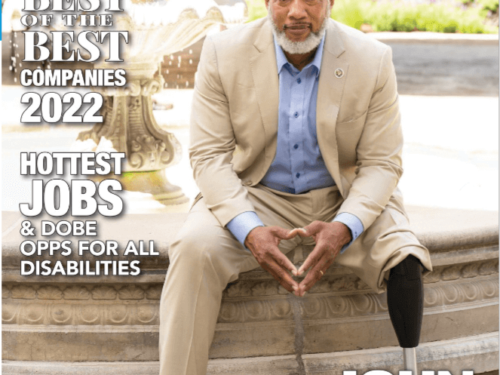

John Register lost his leg while serving in the Army.

It didn’t happen the way you probably think.

This wasn’t a combat wound. This wasn’t a wartime horror. Register, 49, an Olympic hurdle hopeful once upon a time, lost his leg when he was injured during practice. He dislocated his kneecap and ended up having his leg amputated.

[image-shortcode url=”https://johnregister.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/john-running-02.jpg” size=”33″]A longtime track and field historian researched back to the early 1900s to see if there were any other injuries like it but found none.

But in the two decades since his injury, Register believes he has gained way more than he lost.

“Now, I do more with one leg than I would’ve ever thought to do with two,” he said while taking a break Tuesday from the Veterans with Disabilities Entrepreneurship Program.

In Stillwater for a week-long business boot camp sponsored free of charge to the veterans by OSU’s Spears School of Business, Register hopes to learn how to better help athletes who he meets as the associate director for community and veterans programs for U.S. Paralympics. He also wants to be better with his own business, Inspired Communications, which works to inspire and motivate teams of all kinds.

The hurdler who lost a leg hasn’t stopped jumping over obstacles.

Register was a member of four national championship track and field teams at Arkansas in the late 1980s. The four-time All-American did the sprints, the long jump and the hurdles, but when he finished college, he started to focus on the hurdles.

He enlisted in the Army and became part of the Army’s World Class Athlete Program. Making the Olympic team became his mission.

Even with tours of duty in Desert Shield and Desert Storm, Register continued progressing on the track. He made the Olympic trials in 1988 and 1992, and with his times in the 400-meter hurdles dropping about .3 of a second each year, he was on track to have a time that would get him into the finals at the 1996 Olympic trials.

But then late one May afternoon in 1994, Register was finishing a training session in Hays, Kan. He was making one last pass when his left leg landed awkwardly after he cleared one of the jumps.

“Something went wrong,” Register said, “and it just snapped.”

His bones didn’t snap. His kneecap did.

The patella in his left knee ended up about three inches higher than his femur. His leg bent at a sickening angle as he lay on the track. The worst of it, though, was that the dislocation clamped off an artery just behind the knee cap.

Blood couldn’t get to the lower half of Register’s leg.

It took 90 minutes for an ambulance to arrive — to this day, Register isn’t sure why the delay was so great — and then it took a few more hours before he could be flown to Wichita to see a vascular surgeon. It was past midnight, more than seven hours after the injury, when he was finally on the operating table.

“What did me in was time,” Register said. “Without blood, the leg starts dying.”

By the time his surgeon intervened, he could give Register only two options. Fuse the knee, and have such limited range of motion that a walker or wheelchair would be needed to get around. Or amputate the leg above the knee. That would lead to a prosthetic leg, but Register would still be able to walk.

For Register, the choice was easy.

“I knew it had to be amputation,” he said.

Still, the reality was harsh. He lost most of his leg less than a week after posting the year’s eighth fastest hurdle time by an American.

What else might he lose? His marriage? His relationship with his son? His relationship with his parents? His job in the Army? His identity?

A couple days after the amputation, Register went with his wife and 5-year-old son to a playground near the hospital. Not yet fitted for a prosthetic, Register broke down as he watched them play.

Wife, Alice, noticed the tears.

“You know what?” she told him. “We’re going to get through this together.”

That got Register to thinking — maybe he wasn’t going to lose his marriage. Maybe he was still going to be a husband and a father and a son and a military man. Maybe he could even still be an athlete.

“Maybe it’s not about what I lost,” he thought. “It’s about what we gain.”

During his recovery and rehab, Register took to swimming, which had been one of his sports growing up. Someone mentioned early on that the Paralympics might be something he could consider.

Less than two years after his injury, Register made the 1996 U.S. Paralympic team. He swam in the Paralympics in Atlanta, then four years later, he returned in Sydney. But the second time around, he competed on the track. He won the silver in the long jump and set an American record of 17.8 feet.

His journey has been chronicled numerous times over the years. Who doesn’t love a lemons-to-lemonade story like his? And a few years back, Register was riding an airport tram at Washington Dulles with an amputee buddy when his friend struck up a conversation with a gal who worked for United. Her name was Susan, and she had read a story in the Washington Post about a man who’d lost a leg and become a Paralympian, then had seen him on TV.

Register’s buddy smiled.

“I think you’re talking about him,” he said, pointing to Register.

Susan couldn’t believe it. Neither could Register, who gave her one of his business cards.

Last summer while Register was buying a hot dog in Colorado Springs, where he lives and works, his cell phone rang. It was Susan. She had lost his business card after their meeting, but while cleaning out a drawer two years later, she found it. She figured that his number had probably changed, but she tried it anyway.

She wanted to thank him.

When they’d met, she’d been battling breast cancer. She had decided to attack it several ways, including having a mastectomy. It was a tough choice. It was a painful time. But Susan decided to do everything that she could to fight the cancer — because of Register.

“If this guy can be one of the fastest hurdlers in the country and lose his leg and still come back,” she said, “I can surely go through this.”

Then she told Register, “So, I attribute being alive to our conversation and seeing your story.”

Register still marvels at those circumstances. Yes, he lost part of his leg. Yes, he lost his Olympic dream. But he believes he gained so much more because of the hurdles he overcame after he stopped running the hurdles.