There is a famous 30-second Nike commercial featuring the great WNBA player, Lisa Leslie, titled, “You don’t win silver, you lose the gold”.

When I first saw this commerc ial I was like, “Yeah!”

ial I was like, “Yeah!”

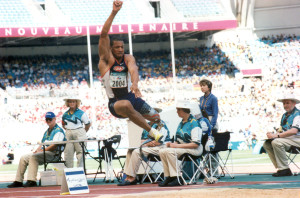

But, then after I won the silver medal in Sydney, Australia in the Long Jump at the Paralympic Games, I was a bit more reserved in my enthusiasm about the commercial. I realized that I put a lot of effort into winning that medal.

Truthfully, I understand where this philosophical thinking comes from and why people would consider the NIKE message a powerful one. Everyone wants to win first place. It does not matter if it is in athletic competition, academic rivalry for valedictorian, or business opposition to win a contract; we all desire the top spot.

I am no different. I want to win.

After further review of my own sentiments I came to the conclusion that I no longer agreed with my previous position. I now believe that this statement underscores a deeper problem in sport and our society, which is an “entitlement” mentality.

I believe in sports, as in life, we earn what we earn, and we win what we win. To take the stance that I lost the gold medal at those games means firstly, I discounted the efforts and achievement of the winner, in this case, Lukas Christen from Switzerland. When he won the gold, he was the two-time reigning champion. He won because he outworked, out-prepared, and out-executed me, by 4.5 inches to win his third consecutive Paralympic long jump title.

Secondly, a statement like that discredits the work that I put in to winning the silver medal. And let me tell you, I did a lot of work to earn that silver medal! 20 years’ worth of work.

Let me break down for you why I earned this silver medal. It all has to do with a shifting of focus, the effort in preparation, and the exceptional execution of the goal.

I competed in two Olympic trials in three different sports and was the eighth fastest 400-meter hurdler in the country at the time before the disabling injury the resulted in the amputation of my left leg.

It took me 2 ½ years to get my nerve back to step foot on a track again, let alone relearn how to run with an artificial leg. It was not until my third year, post-amputation, that I retaught myself how to run again. It was not an easy process.

John getting stronger getting faster

I knew how to train, but I had to figure out my energy system. The energy expended for an above-the-knee amputee is three times that of a person with full limb mobility.

Second, I was ignorant. I did not know what I did not know when it came to the mechanics of artificial knees. For 6 months I was unable to figure out why my artificial leg was hyper extending when I ran. I needed an extension stopper, a piece of metal that stops the leg from going into hyper-extension. I went through three or four hydraulic knees, and 12 weeks of missed training, before a prosthetist from the manufacture told me what was happening.

Third, I was ignorant to the various density of hydraulic fluid in the knee that directly correlates to how fast the knee will return in a running motion. Five days before my long jump at the Paralympic Games, another prosthetist who was watching my practice session told me that I was overpowering the knee unit. In other words, I was running too fast for the knee unit I was using. He called the manufacturer, who overnighted another hydraulic knee with more viscosity allowing me to run faster.

Every athlete that competes in the Olympic and Paralympic games has a dream of winning the gold. For the majority of athletes who are fortunate enough to make it to the Olympic or Paralympic games, that will be the highlight of their career. For a select few, the honored medalists, they will cherish something very few people ever get to experience: having their country’s flag raised in recognition of their efforts and their national anthem played.

Pundits will have us believe the only spot that really matters is the top spot. There is some truth to that. No one wants to be second in a business deal, or be first person out of the job interview, or the runner up in a pageant. But there is a quiet resolve that lies in not winning that pushes one to be better the next time. This resolve is valuable and should never be discounted.

In American society I have seen the entitlement mentality play out in other professions.

One example is youth sports where the attitude is everyone is entitled to a medal. It is almost comical to see this played out in a game of tee-ball or 3 v 3 youth soccer. No one is supposed to keep score. The focus is supposed to be on skill development, friendship, and fair sport. Yet, when the game is over and the kids have run through the parent tunnel. Or, when the oranges or other snacks have been consumed and the mini-vans are reloaded, the very first questions I often hear young athletes and parents are: “How many goals did I score.” Or “how many runs did we get?” “Who really won that game.”

Let’s not kid ourselves, we all keep score.

As an athlete, my thought process was no different. I wanted to win the gold medal. It was not my goal or desire to travel 9756 miles from Northern Virginia to Sydney, Australia and come back with anything less. I do not know of any athlete who goes to a competition looking to win second place.

That is why I believe that “losing the gold” drives an entitlement mentality. The premise negates the work that goes into performance and being satisfied with the outcome of the results.

My ignorance about my new equipment coupled with having to learn how to run again were not easy. Yet, three years after taking my first running steps on my prosthesis, I was the second-best long jumper in the world. I was being honored to represent the United States of America in the Olympic stadium having earned the silver medal! You had better believe that I am proud of that.

My stance is this: We earn gold, silver, and bronze. We also earn fourth, fifth, sixth, or whatever position the result concludes. To say that you did not earn those positions, or that you should have done better, is to say you were entitled to something that you did not deserve or earn.

We earn what we earn.